ActivityPub and Newsrooms: Thinking Past Platforms

The Great Exodus That Wasn’t

After Elon Musk raised profane amounts of capital to buy Twitter by appealing to Saudi and Silicon Valley resentment of the current management of the world’s first and last open newswire, digital editors and news outlet management worldwide were, understandably, shook. The Wall Street Journal reported Ralph Ellison’s rationale for investing a billion (give or take whatever Elon saw fit) as follows: “It’s a real-time news service, and there’s nothing really like it,” he told me. “If you agree it’s important for a democracy, then I thought it was worth making an investment in it.” (Src) News outlets and individual byline-holders alike had evolved whole technological toolkits, middleware markets, and career trajectories around the Twitter platform over more than a decade before these sudden changes, and in large part it can be speculated that it was exactly this symbiosis between news and the Twitter platform that the bulk of Musk’s financial backers wanted to disrupt and rebuild differently.

In the almost two years since, the Great Exodus many were expecting never quite happened: while Twitter’s centrality to news is indisputably diminished, the landscape has gotten more and more fragmented rather than swinging markedly towards a new center of gravity. Just as no “winner” has yet emerged, neither has a paradigm shift yet definitively occured towards decentralized and/or federated models, although both seem to be steadily gaining ground and on track to terraforming that landscape by the end of the decade. Perhaps two years is an unrealistically short time to expect such results, and the balance of power between the Empires of Network Effects should be studied on a more glacial and geopolitical time-scale, as do nuanced shifts in the Modes of Content Production and Monetization.

Even if the medium-term future still feels like a toss-up, news outlets need to be planning their next moves and their long-term direction, carefully balancing engagement today against dependency tomorrow. While a “more direct” relationship to readers that they can own and manage is appealling, reach and monetization are drastically harder to secure in the “homesteading” model, and at least for the near future, the more fragmented and competitive terrain has at least lowered the “reach tax” that global platforms on steadier footing charge publishers for visibility where their readers are already looking.

The purpose of this essay is to overview the technical and architectural tradeoffs in each option on the spectrum from “self-hosted” social to mega platforms, and hopefully to trouble that linear mental model a bit by introducing the idea of an open social data graph cross-cutting that spectrum and undermining its assumptions.

After describing various platforms qua platform, I’ll try outlining how federated self-publishing and a portable social graph based on it can function almost like a shared Content Management System, with a built-in identity layer to power a “comments section” governed locally but reaching globally. Admittedly, the path to monetization or advertising platforms based on this “public option” for open data is hard to predict in 2024, just as it was on the open web in 2004. But for news publishers that can afford to think that far in the future, federation protocols offer a less toothless model for publishing on “the open web” that undermines the winner-take-all “attention economics” that vertically-consolidated megaplatforms used to enclose the commons of the web over the last two decades.

Actual Exodus Data

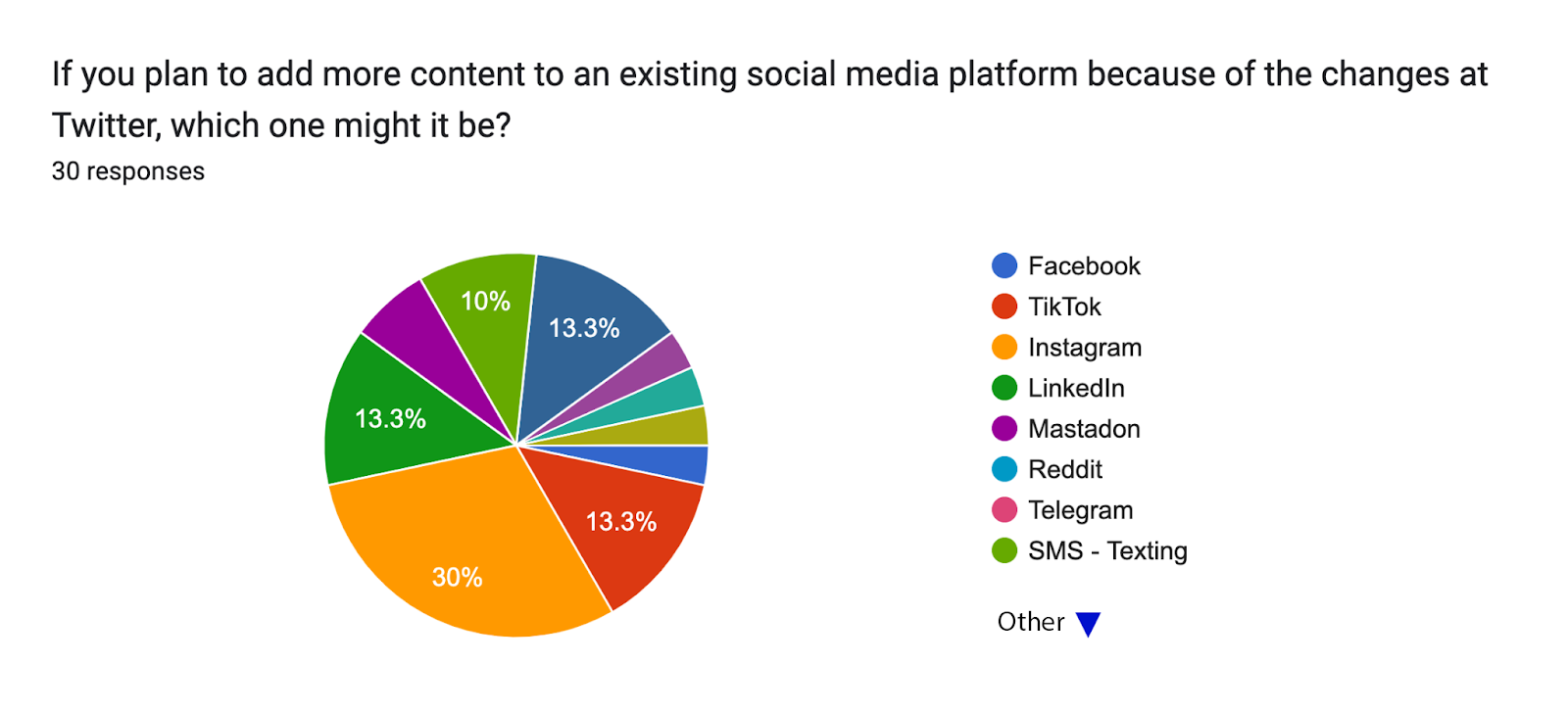

We can begin to situate the post-Twitter publishing landscape by looking at some interesting survey data from the American Press Institute. At the Online News Association in February 2023, the API shared the results of a survey they conducted while the topic was still front-of-mind for online editors everywhere:

First off, some might be surprised to note that for almost half of the parties surveyed, a Meta property (Instagram or Big Blue) was the next-best thing to Twitter and its closest replacement. Others might surprised how many trade and specialist outlets shifted Twitter resources and adspend towards LinkedIn, with its effective industry-targeting and tie-ins to trade show organization, or how many focused on SMS messaging or classic newsletters. Mastadon [sic] hardly registered on the survey, which is not so surprising given that news is a mass-market phenomenom driven by big numbers, big data, and advertising, none of which can really be called capabilities of Mastodon qua software or qua userbase.

My main takeaway from that presentation was that until Elon inflicted his management style and brand safety philosophy on Twitter, the platform had been so useful as to be a cornerstone of online strategy for a wide range of diverse news outlets. Each of those, a year into the Elon era, splintered off to a different platform depending on what audience it primarily strives to cultivate, and what kind of engagement powers its revenue strategy. Throughout its golden age, Twitter had been something like the “public option,” outperforming and outrunning the more tailored “News” platform products that Apple and Google tried to make for penning news outlets into a closer feedback loop with advertising and discovery. One advantage it had over the duopoly efforts to kettle news publication lay in its DNA as a “social media website,” in the sense of an account-based identity system fully of lively, authentic, and empowered users powering the algorithm in real-time like a hive mind.

A less obvious advantage, which I will elaborate on below, is that after so many years of symbiosis between a huge userbase and various recommendation algorithms and search tools, Twitter was sitting on a global data lake without which it could never have become a “democratized news wire”. No future open news wire on a similar scale is imaginable without a comparable ocean of user-generated content and interest-metrics, ideally being ingested and influenced by a competitive ecosystem of algorithms and search tools (rather than a vertical monopoly over them owned by the same private concerns controlling access to that underlying wealth of historical, mostly-authentic data).

What We Lose When We Lose Twitter

Over the years that Twitter was ossifying into something like critical infrastructure for information distribution, it achieved a kind of invisibility and was taken for granted in ways that few commentators outside politics and news really recognized. A “tweet” became a kind of low-level primitive for the web, so low-level that it can be hard to even remember this evolution or name the attention pathways and copycat UXs it created. Tweets beat out “Facebook posts”, “Reels”, “Carousels”, “tumblr threads,” “[Medium] blog posts”, “subreddits”, and all the other atomic units of social media for mindshare exactly because it was easier to think of them as units of “content” divorced from their static, mostly unchanging presentation on the website or app. Tweets were made for screengrabbing and linking-to, rather than for bringing you into a walled garden, much less an authenticated one.

In economic terms, I would argue that twitter.com (the website and mobile app for reading, writing, updating and deleting tweets) was one of the more valuable things he acquired, even if his confused attempts to rename, rebrand, and redesign the website imply he does not personally agree.

Even more valuable, however, is the longevity, the authenticity, and the orderly data language structuring that huge corpus of golden-age tweets.

This corpus powered all the interal algorithms and tools that made a well-oiled Twitter neutral enough to be adequate plumbing for news, and it was key to Twitter’s value.

While Silicon Valley commentators have historically derided Twitter for not finding a monetization model adequate to its operational costs after all those years and CEOs, that corpus alone (even if all the humans and bots stop using the platform tomorrow) will still be worth a fortune decades from now, after every open platform and comments section is flooded with generative AI runoff.

I believe Twitter was and still is a data and informational substrate in ways that no other “social media” has yet become largely because it provided a “mode of publishing” that took root and became part of the furniture of the internet, eclipsing the mere “real estate” of twitter.com where people went for decades to do that kind of publishing.

The “tweet,” as a kind of intuitive and universal user-experience primitive, survives twttr.com just as the “soundbyte” survives the decline of broadcast radio and television, remaining intuitive even for generations that need “broadcast” explained to them by a historian.

In this sense, we need to consider the difference between a tactical and a strategic “replacement for Twitter”, in the sense that tactically news outlets need to engage their readership today and build revenue around that relationship yesterday.

In the long term, however, news outlets also need to make a strategic bet on “where” the most, best “tweet”-like things (at least in the eyes of their readership) will be ten years from now, or what technosocial system writers and editors will game to get reach with their little tweet-like content-teasers and conversational threads.

Or more precisely than “where”, we might ask in what giant corpus and in what data model these gajillions of grains of content-sand will form giant dunes worth mining and sifting and navigating. I think it is misleading to think in terms of “monthly active users” and growth charts– these are the metrics of commercial platforms and products (alt link), but they are also the metrics of Goodhart’s Law, projecting onto the future a market with the same dimensions and groundrules that govern commercial platforms today. (And those groundrules might change soon, with a little luck and another few anti-trust wins!) While “user metrics” and attention as conventionally measured are a crucial part of what drives and sustains engagement on the competing commercial platforms generating their respective content data lakes, thinking about the long-term health of news (and of the internet itself) requires us to think past (and below) platforms, or at least to look orthogonally at their informational runoff, which in large enough quantities becomes its own center of gravity and takes on a life of its own.

The Cowpath Beneath the Platform

In the vernacular of today’s youths, who grew up swimming in the waters of commercial social media, Twitter is the lightest-weight, easiest-abandoned, most novice-friendly way of establishing a “presence online.” Twitter accounts can be earnest publishers, sincere consumers who want to respond in good faith on the threads of others, invisible lurkers who train an algorithm to surface the content they want to consume without producing a single tweet in years, or insincere trolls and spambots who are at cross-purposes with the OPs of every thread they post to. In all of these cases, however, each account is a kind of micro-ledger of events published into an extremely public and searchable corpus floating in an ocean of other content it links to from every tweet. To create a Twitter account is to hang a shingle, knowing that you will be easy for others to “find” only in proportion to how much engagement you garner from everyone else. Twitter was engineered for decades to be coextensive with “the web” rather than to be a platform with a perimeter around it, giving some sense of semi-public obscurity or even private-mode occlusion, a feature which Meta properties had made table-stakes for more properly “social” media over a decade ago.

By comparison, a typical [young] user today doesn’t feel like they are signing up for a web presence directly on any social media website:

- creating a Reddit (or Lemmy) account feels like signing up for a debate club, or some kind of academic senate where the marketplace of ideas is tediusly voted up and down

- creating an Instagram account feels like hiring a brand manager whose first piece of advice is to take out an ad in a fashion magazine

- creating a Facebook account feels like taking out a halfpage ad in a [Gannett-owned] smalltown local newspaper

- creating a Tumblr account (in 2024) feels like getting a booth at an anarchist ‘zine fest– public, but not visible or mainstream in any sense

- creating a Github account or a LinkedIn account feels like getting an Employer Identification Number from the IRS, or buying an Amazon Ring, the footage from which can be analyzed by any future employer and the various machine-learning products SaaS products it enables on its Azure control panel.

Partly, my argument here is a bit of a sleight of hand, because the comparison of Twitter to “properly” social-media platforms is a bit of a category error; despite its initial founders’ social-first designs (see Lorenz, for ex.), Twitter really hit its stride (or spun up an organic user-growth flywheel, to be more precise) when it found the right balance of fun and micro-publishing, shit-posting and shingle-hanging, enabled by powerful recommendation engines and feed-sorting algorithms for a diverse set of user stories. In this sense, it might make more sense to situate Twitter not as the most universal of social platforms but the simplest of publication and syndication networks, by being more accessible to more kinds of publishers and allowing readers to “follow” just about everyone they might want to. Here we might think of Twitter as a far simpler, more accessible version of software that organized firehoses of open-web content: Google Reader, user-friendly general-purpose RSS clients, and the mythic webring salad days of the pre-corporate web from which spawned the neologism of the “[we]blog” in the first place. Squinting a little, we could call Twitter the freemium-model, lightweight, toy version of a more customizable “content management system” like WordPress, which is one of the oldest pillars of the modern web, now powering anpit 40% of it and counting.

The most salient aspect of Twitter from the perspective of news is its “democratizing” horizontality, by which casual readers, loyal subscribers, individual by-line reporters, their reply-guys, whole desks or even whole beats across many outlets, and whole newspapers all stand on equal footing before the algorithm and moderation policies. (Well, almost equal, modulo those pesky color-coded stars that have iterated so quickly as to lose all meaning since Musk started moving fast and breaking everything.) This radical horizontality is a pretty hard illusion to pull off, of course. The trick to pre-Musk Twitter was a massive and expensive armature of complementary sorting mechanisms: algorithmic surfacing, search, moderation, and blocking/hiding unwanted or low-quality content creates a usable ocean of content to swim in for all user-classes, obfuscating the exceptions to its seeming horizontality and neutrality. Making one giant comments section for everyone’s micropublications definitely inherits the massively expensive liability of all social media, in that it is made of humans, so if you want anyone to want to spend much time in your little corner of it, you always have to hide a significant percentage of them from one another.

Twitter could be thought of as the simplest-possible, most syndicatable, portable, dumbest-possible data model for publishing, and thus the hardest to kill, the cockroach of CMSs for powering a different 2-digit percentage of “the web” than WordPress manages (measured in individual human participants rather than in domain names, that is.)

Nothing Scares Off Capital Like Utility Regulation

Which brings us to another low-level building block of the web so basic as to be invisible to people who live and breathe it everyday: the ICANN worldview. By this, I mean the almost universal impulse (up and down the spectrum from industry insiders to the most casual of web users) to think of each domain apex as a “real address” on the internet, and every other kind of actor or identity on the web as a mere tenant renting or otherwise borrowing “space on the web” from one. The extended metaphor of real estate for the ICANN “namespace” stretches back to the earliest “dot-com Boom” years in Silicon Valley, but has by now been globalized along with the rest of the quirks and worldview of that time and place.

Central to this view of ICANN namespace as real estate “ownable” (technically, leasable) by Captains of Industry is the entirely US-style property rights that govern that namespace; despite all the multi-stakeholder and performatively international governance of ICANN, the domain-name industry makes it really easy to think of the internet as “real estate” on the Angloamerican legal model. This leads to a kind of universalized and naturalized 1:1 mapping of “real addresses” to legal persons (and the occasional hobbyist nerd), which is now so foundational to the entire web (since at least the dawn of O’Reilly’s “Web 2.0”) that it can be hard to even think outside of it. In the meme above about an internet comprised entirely of screengrabs cross-posted between “four websites,” we see how these platforms (and the “websites” mapping to them 1:1) jockey for a kind of mindshare olympics. This axiomatic approach to web identity has been entrenched further and further in tandem with the dominant mode of web economics (governed by the extended metaphor of “properties” on a Monopoly board and users as tenants).

The economic model this identity paradigm created and maintains is extremely winner-take-all and as such, is getting harder to sell to the global middle-class as it create ever-larger empires lead by captains of industry more powerful than sovereigns. In this game-theoretical mode, how many humans visit or are familiar with a domain apex per month is a pretty good metric for how much mindshare it has in the human world in general, all things being equal and economic actors being rational and all that jazz. This ICANN-refereed competition for eyeballs has reigned since Silicon Valley started pumping money into zero-sum brand warfare decades ago, evolving hand-in-hand with a progressively more domain-bound security, privacy, and integrity model for the modern browser. (Over the same years, those same advertising empires mergered and acquired their way into a governance over the browser and the web platform, overwhelmingly dominated by overlapping duopolies at every layer of the online economy, but that’s a story for another day.)

We could think of the “Web 2.0 cycle” (roughly mid 2000’s to mid 2010’s) as a protracted competition between “individual websites” on the one hand, struggling to own and build engagement on their small plot of land, and megaplatforms housed under a single web domain on the other, aggreggating and synthesizing vast amounts of engagement into data-brokerage empires, monetizing not just their own content but that of the rest of the web. It feels like a cycle that came to a close because the latter won a pyrrhic victory, assuming such an outsized role in the economics of the web that the seemingly infinite growth slowed as the rate of profit fell, while the scale of this epoch’s externalities and liabilities caught up to its winners. What’s more, these mega “websites” are increasingly beset by escalating anti-trust challenges andmassive liabilities that their economies of scale increasingly struggle to outrun (not least of which are the political and ethical quandaries inherent in moderating enduser-generated content on a global scale).

Servers and Sources of Truth

Coming back to news outlets, the division of resources between “one’s own website” and publication channels and one’s accounts on “someone else’s website” has evolved and transformed deeply over the last 3 decades, in parallel to (and rarely independent from) the shape and regulations on web advertising that crosscut the distinction anyways. The pendulum is swinging back a bit, as regulator dreams and enduser desires alike seem to be pointing towards more domain apexes and more local or bottoms-up control web-wide in the coming years, and some kind of guardrails against hyperconcentration of advertising control and distribution control. Like any other attention business, news outlets nowadays juggle what portion of their budget and worker-hours to devote to each platform, what portion to spend on reader feedback channels that they can nourish and control more directly, independent of the direct or indirect role either plays in their revenue story. And this calculus is changing fast, for a number of reasons.

Fundamentally, the platforms are retreating from an earlier position of self-centering, pushing various liabilities (from censorship to moderation to toxic-data reporting to misinformation to AI-generated spam) back onto “local jurisdictions” and property management companies and individual owners of managed properties and civil society groups. As “artificial” “intelligence” floods any less-than-perfectly bot-proofed and sybil-proofed mass communications channel with noxious chum and vapid arguments between formalism-spewing summary-bots, megawebsites can suddenly collapse under their own weight, their fragile defense mechanisms outgunned by cheap, powerful, and inherently adversarial software. The economies of scale break down completely when a billion humans share one “website” with 2 billion, rather than 2 thousand, bots impersonating humans. Our introductory deal is over, and suddenly, no one wants to be in the business of domain apexes delivering content neutrally and reliably– the “source of truth” industry is disappearing fast.

In a way, Twitter was the last platform of its size that could credibly claim to be neutral enough not to feel like “someone else’s website,” a for-profit global mega-platform that didn’t feel like one until its hostile take-over under new management. But now the music has stopped and we have to wonder: which elements of that now historically-impossible bundle matter most? Pick carefully, especially if you’re bringing home any or all of the “social” functions previously hosted in the massive communications chicken-farms of yesteryear.

Each Server a Variously-Unbundled Microduchy

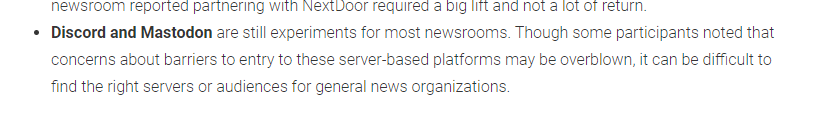

In the American Press Institute poll above, many news outlets described their journey to build close-knit communities on “their own servers.” The presentation limited itself to only the two most popular forms that self-serving took in 2023: Discord servers and Mastodon servers.

I will leave Discord aside for the rest of my argument because I feel strongly that a different, more show-stopping category error pushes them (and Slack) squarely out of scope. Not only are both of their data formats proprietary and their code closed-source, but their commercialization strategy increasingly evinces symptoms of the same shareholder-value-driven enshittification vectors slashing and burning Reddit in realtime, with Slack similarly pressed to extract value from captive userbases. Unlike their “open-core” competitor Discourse, each server in Discord or Slack is not public in the literal sense of published to the open, unauthenticated internet, nor public in the data-engineering sense of publishing in an easy-consumable, standardized, portable data language that can be brought over to a self-hosted or competitor-hosted service.

Mastodon, on the other hand, is something like a reluctant platform, or a “locked-open platform” in the most generous of readings, in that it has exactly the opposite characteristics: the data language in which each Mastodon server encodes all its human activities and publication events is a dialect of ActivityPub, a 5-year-old standard designed in the open at the worldwide consortium. Furthermore, the default (and most robust) configuration of Mastodon is for Twitter-like publication readable by unauthenticated users. On the “write” side, each Mastodon is a tiny feifdom controlling what gets published and what gets rejected, deleted, or blocked; on the “read” side, each Mastodon shares what it publishes freely with every other Mastodon (and many other services as well), making a kind of open-web for the outputs of each fiefdom. This separation of powers makes sense considering that Mastodon’s initial mission, before its data language was even standardized by “averaging” it with two other locked-open social projects to create ActivityPub, was to clone Twitter after Twitter closed off its API and “locked down” its servers to only be accessible from twitter’s own website and mobile clients.

You could say Mastodon rewound history to the point at which Twitter started consolidating power in its website and instead chose to consolidate power at the “Subreddit level”, empowering moderators and allowing communities to self-organize and self-govern as close as possible to the site of content generation. Technologically and economically, this splintering the network into thousands of servers that each design and enforce (and shoulder the liabilities of) their own trust and safety systems. They also opt into and out of federation with other interoperable servers in a completely patchwork and often gossip-based or probabilistic method, as researching those thousands of yes/no decisions and maintaining them over time would be an infinite resource quagmire (and growing geometrically with the growth of the network). Bundling so much of the human and social (and compliance) dimensions of “running a website” at the level of the server leads to an odd kinds of subsidiarity politics: imposing some kind of Mastodon-wide standard for speech or civility (or even for, say, “terrorist content” norms) would be like imposing a code of conduct on a thousands house parties at once. All the credit should go to groups like iftas.org for trying to establish more scalable norms in this paradigm, but it is slow-going work retrofitting standards and norms onto the deliberately heterogeneous patchwork of today’s Mastodon population.

There is another major difference between Mastodon and Twitter, however, and this is painfully apparent in the world of news professionals that have honed their craft to optimize algorithmically-boosted reach:

Mastodon does not have an algorithm, or a particularly useful “global” search, much less a central party that could be paid to place ads globally against that search, or boost a given piece of content in algorithmic or hashtag-generated aggregation mechanisms.

(By “global” I mean across all Mastodon servers, but even if settled for “global” meaning across all servers within X server-to-server connections of a given server, there is still not much in the way of comprehensive centralized indexing).

Global reach, global search, and advertising were specifically not design goals of Mastodon, and even the concept of a “feed” gets thrown out with the bathwater in many accounts of its history and goals.

Being searchable on today’s Mastodon’s servers requires a double opt-in (by server management AND by each user), and the Mastodon developer community has been hostile even to “aftermarket” application of algorithmic feed-sorting to the Mastodon server stack.

So while algorithms and more powerful global search over a substrate of ActivityPub data from many Mastodon and non-Mastodon servers is entirely possible using non-Mastodon ActivityPub software… that hypothetical software isn’t really available in production today on any server that a newsroom could just install and host at its own social. subdomain.

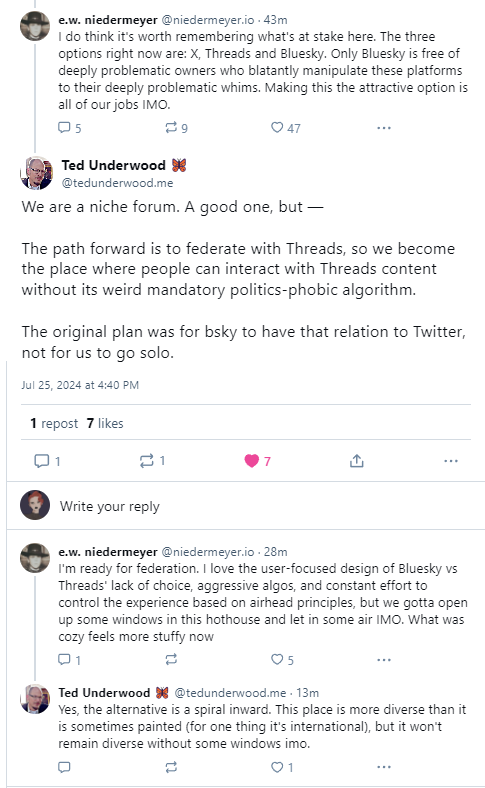

Sidebar: The Alternate Fediverse of BlueSky

Contrast all of the above with BlueSky, which is showing no signs (so far) of early-onset pre-enshittification and is credibly friendly, at least in the medium-term, towards independent businesses exploring business models within and on top of its network and open-source code. It has even promised to federate using its own federation protocol that deliberately reinvents much of ActivityPub, making it a kind of alternate-fediverse on simplified rails that are, to date, not getting that much independent usage. This alternate federation paradigm is in its early days and thus almost as hypothetical as a Fediverse-wide global search or reach guarantees enforceable enough for news outlet usage. While 2024 has seen considerable growth in alternate clients (with some innovation at the “AppView” level), BlueSky’s identity servers and relay servers are still effectively the only utility providers involved in the nuts-and-bolts of providing their service and servicing their “firehoses” of content. (A space has at least been deliberately and publicly carved out for future alternate AppViews and independent Relay firehoses, although the economics of how long they take to develop remain to be seen.)

Until newsrooms can self-host “ATProtocol”-powered social. websites that they fully control and federate to the bsky network, their options are still basically to have an account in the bsky network with credible promises of future portability, or stand up a Mastodon, or use some other kind of ActivityPub software to manage its content, and the users it provisions with long-term, moderately-portable identities.

It’s worth noting that self-hosted “social servers” (and to a lesser degree, Discord servers) enable highly-configurable special privileges or tiers for users at different levels of loyalty or subscription, which is an important axis on which to compare a future “self-hosted” form of whitelabeled and federated BlueSky to Mastodon or other ActivityPub social services, alongside credible portability, cost-per-user, stickiness, and of course monetization or revenue options.

In many ways BlueSky today feels (to a non-journalistic user) like the closest replication of pre-platform, pre-open-API Twitter.

It even has a UX and a userbase that both feel like Twitter’s did before it become a general-purpose information pipeline far-reaching enough and useful enough to double as a newswire and free academia.edu.

Honestly, newsrooms could be forgiven for “waiting and seeing” how things develop differently the second time around, with a novel and minimalist federation protocol and open-graph data language:

it genuinely could turn out to be the best of all worlds, or the best rearrangement of the elements that Twitter evolved (largely on accident) in a different sequence.

But tactically, anyone migrating from Twitter to BlueSky in 2024 feels like they are accepting a major loss in reach, almost as major as moving to a self-hosted Mastodon.

It is a choice between two different orders of operations, two different reshufflings of the Twitter playbook being re-run in a landscape that has since changed.

Threads - Selling Picks and Shovels from the Center of the Chessboard

There are many more options than just those two, offering different subsets of the Twitter system with different roadmaps for reaching parity on the rest. There’s an entire garden of forking techdebts that we call the Fediverse, which are variously accessible to the user of Mastodon (or Threads), and variously functional, many of which I will be covering here.

Today’s Fediverse is a vast, unfinished Linux of networks that mostly interoperate and mostly “work” in the way that Linux distributions “work”, i.e. not at all, at least by the standards of the mainstream consumer used to what Apple and Amazon call “just working”. Mastodon (the platform) is actually very distinct from ActivityPub (the data language), which means that while users of one Mastodon server can “follow” and interact with users on any other Mastodon-compatible server, they can also follow (with variously degraded service and a subset of supported features working as expected) RSS-like content streams from elsewhere in the ActivityPub universe, which is actually quite vast and heterogeneous.

In the “full Mastodon API support” category we find Zuckerberg’s newest property, Threads.net.

Its top-level domain (.net) is a subtle nod to the humbler, more utility-like aspirations of Meta’s “public option” and, realistically, it is the most viable Twitter replacement in 2024, at least from the perspective of news outlets looking for maximum reach and minimum risk.

(I think that if the American Press Institute ran the same survey today, Threads would take a 2-digit percentage of the pie chart, but that’s just tendentious speculation.)

Meta may be slightly less credible than BlueSky in its commitment to federation and open-platform economics (by dint of Meta’s size, governance model, and track record), but at least ActivityPub as specified today has certain minimal affordances for and guarantees of portability:

even today, a publisher can switch relatively smoothly from publishing on Threads to self-hosting a Mastodon without losing too many features or followers.

Threads may not be as wild or organic as BlueSky, or as addictive or libidinal as Instagram, but that’s OK, it’s not trying to be! I suspect it’s not even trying to be profitable, really, or glamorous, or addictive, or innovative in the conventional sense, except insofar as driving hard into the center of the chessboard and being a no-frills loss-leader public option that grows the pie for all of of social media (or at least all of the Meta family of concerns). It may not be immediately obvious what’s so innovative about this, but one intriguing reading of this business-model innovation posits that as federating with Threads becomes more and more valuable and attractive to the scrappy, bootstrapped, self-hosted servers of the grassroots Fediverse, Meta (or some cottage industry paying Meta for the privilege) could start offering moderation and compliance with Threads’ high standards as a commodity service, billed per-user or per-post.

Coming back to the forward-looking newsroom manager, I would argue that Threads deserves a second look NOT because of its size, its reach, its capitalization, or its market share but its ambitious gambit to reinvent the game and strike a new admixture of silo and open platform.

Threads is running a different race than it appears to be:

it is trying to beat BlueSky and Mastodon and LinkedIn not to profitability or to critical mass or even to centrality, but to utility, or to put a finer point on it, beat them at becoming an informational utility at global scale, infrastructure as invisible as golden-age Twitter was and Instagram and Big Blug both failed to be for all their overt .com producty-ness.

A huge part of this is that unlike Mastodon, it brings world-class global indexing and search and algorithm expertise that it is transfering over to a broader, federated data plane of Threads + Mastodon + GoToSocial (an independent re-implementation of the Mastodon-API), and hopefully soon many more ActivityPub flavors further from the Mastodon API center of power.

Embracing federation this openly means taking the hit of enforcing its quality, brand safety, moderation, and compliance norms on content generated by users it doesn’t even serve at the point of federation firehose, which (in business terms) is kind of wildly innovative and novel for a company not known for adopting open standards, open networks, and even a theoretically portable, open social graph.

(Or perhaps armchair pundits like myself give Meta so little credit on the open standards front only because Facebook never publicly commented on its earlier attempt to corral friendly competitors to embrace an earlier version of the ActivityPub federation standard in 2008-2009 before walking away from the idea.)

One particularly user-hostile feature of the Fediverse’s radically decentralized, data-first federation to date is that on the level of end-user experience, users have no guarantee when they see a link on their “home server” pointing to, say, unfamiliar.social or @someguy@bumblefudge.com whether it will be a Mastodon link, a non-Mastodon ActivityPub link, or a third unknown thing.

To my knowledge no ActivityPub software to date has sorted the namespace of HTTPS URLs into degrees of AP parseability or conformance and surfaced that to the end-user as a different-colored link or other cue that any link might take them partly or fully out of the fediverse and onto the old silo-web.

Something I love about the Threads product is that it brings these kinds of user expectations to the forefront of discussion and makes them table-stakes of federation with the biggest body of users, incentivizing upgrades to the system and making a Feta-verse within the Fediverse (itself named satirically during the golden age of Zuckerberg’s earlier rebrand).

Whatever the long-term rules of the Feta-verse within the Fediverse will turn out to be (they’ve been very quiet about what advertising and revenue-sharing might be possible in their federate future), having a megacorporation with some utility-experience raising the bar for their subset of federation will definitely expand the vocabulary and business model options for the rest of the fediverse directly and indirectly.

Newsrooms should consider Threads an interesting alternative to Bluesky, Instagram, or Mastodon, since it falls somewhere between all three in vibes, user experiences, and growth possibilities. What’s more, it gives partial access to readers on both Instagram and Mastodon in different ways, and who knows, maybe some day it’ll even partially have touchpoints or bridges with BlueSky as well, or some other networks? Whichever of these platforms continue growing for the next year or two are likely to experiment with at least partial publishing interoperability, if not user-interaction interoperability or federation, so the choice between them is not particularly irreversible or zero-sum.

Oops I Forgot To Mention Another Big Chunk of the Fediverse

Earlier, I mentioned in passing a broader Fediverse that eschews or ignores the Mastodon API, with its sometimes tendentious interpretation of the ActivityPub data language that bends it to the needs of its inward-facing UX goals. (In Mastodon’s defense, it has naturally spent the last many years prioritizing the user experience of its loyal and loud users over an academic interoperability with a smaller userbase in the non-Mastodon fediverse, primarily comprised of its exiles and ex-users until Threads came along to legitimate many of its choices.) Threads has, for the time being, something like 90% of the “active users” of the Fediverse, and before it joined, Mastodon-compatible servers had somewhere around 70 or 90%, but the remaining “rest of the Fediverse” is actually quite significant, growing rapidly and quite important to consider separately for many reasons.

One growing “neighborhood” of the Fediverse today is the so-called “Threadiverse” (no relationship to Threads!) which takes the basic shape of Reddit (link aggregation with upvote/downvote-sorted comments sections). As Reddit has enshittified, pivoting hard into stakeholder value at the expense of its previously autonomous communities and hardballing search engines looking to buy access to their valuable datasets, a much larger exodus of users (particularly the most value-generating power-users, the “mods” or moderators, as well as a good chunk of the non-mod daily posters) has created a massive population of exiles looking for their fix of a UX they grew addicted to over the years. These exiles are increasingly finding homes on indie Reddit-clone servers, or in the case of many veteran subreddit moderators, even pay out-of-pocket to stand up their own. These are federated to those of other ex-moderators, quickly constituting a DIY replacement for a previously robust and deeply-entrenched community, even without the assistance of corporate overlords and their powerful search, sorting, bot-detecting, and other tooling. Like Mastodon, these Reddit clones trade independence and self-governance for the burden of self-hosting, plus a weaker form of “global” search, closer in essence to a search of “this server and the ones it swaps data with.” Also like Mastodon, these sites (Lemmy, kbin, and now NodeBB) enable patchworks of servers that run their own (customizable, often invite-only) user systems and moderation policies to cross-publish, cross-comment, and generally share data and users, owning their own infrastructure but still participating in a broader data lake of upvotes and downvotes and threads. (A fun detail for the data nerds is that since servers and federations are fragile and sometimes fleeting, they’ve had to elaborate their own resilience mechanisms for displaying cross-server threads that survives server deaths and defederations, a fun distributed-systems UX problem to ponder!)

While the Fediverse heirs to Reddit might be less directly interesting to news outlets than other Fediverse form-factors and “neighborhoods”, it is worth noting that unlike the original Reddit, there is a built-in upgrade path by which the Fediverse Reddit threads can be read, followed, and participated in from a non-Threadiverse Fediverse application willing to do extra work displaying it properly and/or separately. The neighborhoods can be as distinct or as merged as individual servers and clients choose to make them over time, because the underlying commonality of data records they generate and share makes the translation and interpretation issues relatively manageable. You could think of Mastodon and Threads as distinct platforms joined at the hip, with slightly different features and governances, but almost completely interchangeable data flowing through the pipes; the same could also be said about Lemmy and kbin, and a little bit of fancy plumbing could federate the Threads-plus-Mastodon federation to the Lemmy-plus-kbin-plus-nodeBB federation, since it’s all ActivityPub data flowing through the pipes, modulo a few use-case-specific extensions. In this sense, while very few news outlets will be standing up their own Lemmy instance any time soon, there is a very real sense in which case the health of Lemmy and kbin’s community contributes to the health of Mastodon’s and Threads’ network effects as a kind of indirect ally and user-sharing agreement. More concretely, improved interoperability in the coming months and years could mean more user-sharing and cross-platform “comments sections,” for better or for worse (and probably highly customizable regardless).

Oops I Have Even More Fediverses To Explain

Even further afield, and probably much more relevant to news outlets thinking on a longer timeline, are three platform giants incrementally lumbering towards Fediverse interoperability as fast as you can expect three extremely complex codebases to move without breaking anything vital for their millions of users. These are:

- Discourse, the open-source, self-hostable, and enterprise-hostable forum software that powers a huge chunk of the subject-matter-specific Knowledge Bases of the world, is quite far along in rolling out ActivityPub support for any Discourse user that wants it. (Fun fact, ActivityPub developers use an ActivityPub-enabled Discourse server every day to debate protocol improvements and UX ideas, and some day Ethereum developers might as well.)

- Wordpress, the most widely used and load-bearing Content Management System in history, is rolling out support to make any WordPress “followable” from any ActivityPub client, and working out ways to even make ActivityPub-powered federated comments sections available to blog-style sites, one of the original goals of the standard dating back to 2010.

- Similarly open-source (or at least, Community-Licensed, for the nitpickers) and self-hostable Gitlab, which has long beaten Microsoft-owned GitHub in just about every category except visibility, social-media-like network effects, and free-tier subsidies, might finally see some progress on at least one of those categories by enabling ActivityPub, making repositories or packages followable actors for people that want to be notified about (and comment on) binary publication events or security disclosures. (Note that the even more indie option, Forgejo is also working on ActivityPub support, which of course opens up the possibility of a whole Gitiverse as well, or maybe Forgeiverse?)

An Actual Everything App, or even an Embarassment of Overlapping Everything Apps

One of the most esoteric aspects of ActivityPub as a data standard and minimalist messaging protocol that I have only hinted at until now is that ActivityPub isn’t, at its lowest level, anything like a Social Media application or even a general-purpose language for building diverse social applications. It’s actually something far more generic: a messaging protocol somewhere between e-mail and RSS (RDF Site Summary), which despite a somewhat fumbled standardization history is still very load-bearing after all these decades since it’s the basic mechanism by which podcasts publish new episodes and podcast software can interchangeably subscribe to them.

This means that while Twitter-clone Fediverse and Reddit-clone Fediverse and Git-collaboration Fediverse and Wordpress Blogiverse can all support tailored apps, it’s also technically imaginable that someone might just use a hypothetical “Threads suite” to access all of the above without leaving their Instagram/Facebook account. If that sounds too dystopian for you to stomach, think of how many email apps you can use for how many email accounts, and still have the basic concept of “emails” amassed in interoperable archive formats, but for… every other kind of social interaction and message and subscription and the like.

This radical commonality of underlying formats means that not just one Everything App but many Almost Everything apps will probably coexist for the foreseeable future. The open-data substrate of ActivityPub data (or, for that matter, Lexicon data, the BlueSky equivalent) can be thought of as an Everything-layer for publication: instead of a zero-sum game to control and monetize that shared data, applications will have to compete on comparative utility to take any subset of that everything and any subset of the shared userbase. Business will find a way, and realistically so will advertising, but at least the data and the attention-graph of each account (if not the social graph properly speaking) can stay locked open and accessible by multiple authorized clients and widgets and services. Or, hippie dream to end all hippie dreams, the pendulum could swing even a little bit in the other direction, and the web as we know it might just get a bit less consolidated, less corporate, and less advertising-driven.

This shared-data substrate might be too big for any one Everything App, too big for even a hundred Major Global Websites and App-store monopolies to extract even half the value it generates. The arc of economic history might bend meaningfully towards decentralization, of the kind that actually benefits the information businesses and independent actors in the system. Who knows, maybe the entire web could support multiple news-wire-like channels that share infrastructure and cooperate, instead of a cut-throat competition between attention-captivity ponzis.

In such an economy, information businesses could stick to their core competencies and worry less about this or that platform’s algorithms and this or that platform’s reach-buying economics– platforms might actually cede some centrality to protocols here, placing a ceiling on vertical consolidation. Information businesses could just communicate more directly with their readers (in a more advanced version of the substack/ghost model), or more precisely, outlets and reporters could just deliver straight to each reader’s post-email, powerful ActivityPub inbox, accessed by robust combinations of clients and servers that sort, triage, and manage it. (In an alternate, better universe, our email inboxes might have been just as co-managed, instead of consolidating to a world with barely any competition for gmail and company-emails, but that’s a subject for another, even longer essay perhaps.)

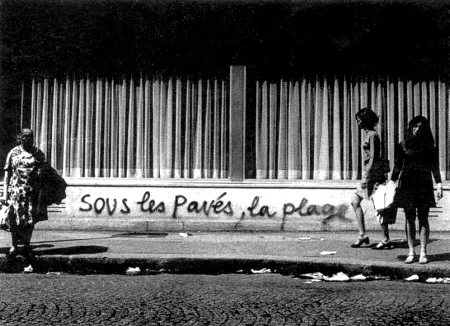

The Beach Beneath the Pavement

In a way, the basic premise of Mastodon and Lemmy and other self-organizing, bottoms-up configurations of autonomous and omnipotent “servers” arrived almost 10 years too soon to be viable economically, and got mistaken for dead-ends due to just how inclement that climate was in those years. It sounded like a 1968 hippie fever-dream, in the cynical 2010s, to standardize in advance a data language that would be the bedrock information-plumbing layer of multiple open platforms on which multiple future products would have to find their way to market, committed in advance to an open graph of public data in common. In the golden age of platforms that were also websites, that were also data languages, that were also horders of closed social graphs, locking open and sharing even one of those four layers was a hard sell and an uphill slog! Decoupling all four to be independent layers of a stack that had to somehow cooperate to compete with the hyper-monetized Goliaths of the day was, even more than publicly sharing the “crude oil” of social data was unthinkable back then.

But now, as giant websites are incurring giant liabilities and disappointing their once delighted end-users and their general counsels alike, it’s not looking so impossible to federate and share utility costs. Calls to commoditize user-management and share infrastructure with grassroots, self-funded community infrastructure is coming from the most surprising corners of Silicon Valley these days, for the strangest of reasons (sadly none of which have to do with appeasing the FCC). Even if advertising is still as oligopolous and mediated as ever, at least their engagement operations are loosening their grip on the readers of media and gradually disintermediating themselves from the telemetry-obsessed, silo-filling marching orders that made them so unpopular with regulators for decades. The Goliaths of yesteryear are suddenly all too eager to decenter themselves, if not completely disband the layers of their monopolies into distinct legal entities that orchestrate totally different platform economics where once they operated in lockstop. The primitive accumulation and vertical monopoly phase is over, and this is great news for journalism and information businesses generally regardless of how uncertain the next ten years will be.

It’s terrifying, at least tactically, to face a power vacuum, but it’s also great news that a generational hegemony is just running out of steam and giving up. A new age is dawning in which it will be increasingly less profitable (and bankable) to fence and horde network effects and information flows. Say what you will about ActivityPub as a global data language, and I am the first to admit it is a wonky Frankenstein of a standard today, it is at least a workable Esperanto, and a lot easier to hold my nose and work with than a global [data] empire of California accents on which the sun never sets. The W3C has certainly shipped worse.

I don’t even worry about whether BlueSky will be more succesful sooner by federating those 4 layers in a different order, or by inventing its own streamlined data language, because either way the end result is immensely better than status quo, in that whichever federation protocol wins, we win as end-users. Either way, the economics of information pipelines shift in a better direction, with more regulable and accountable utilities (“firehoses” and “clearinghouses” and “archival nodes”) replacing today’s vertically-consolidated Standard Oils of social data. Everyone can only stand to benefit from that: today’s vertical monopolies are holding our grandmothers’ inboxes, our local newspapers’ loyal readers, everyone student and voter’s primary and secondary sources, and our baby pictures hostage. However federation proceeds, it’s a kind of de-growth and antitrust jubilee, loosening the strangehold that hyper-consolidated advertising has had for decades up and down the value chain of information industries.

And I’m pumped, dear reader, even if I’m a little scared I won’t have a few American companies to blame for every outbreak of misinformation or every election obvious swung by some targeted filter-bubble ad-spend. It’s the only future in which I still want to have a computer or a smartphone, really.