Of Grammatology: IPFS as Language Family

People often ask me what the future holds for IPFS, or how much community and/or market demand there is for further development and hardening of IPFS. To which I always ask: which IPFS are you referring to?

IPFS for me is not a network, or a toolchain, or even a set of technologies: it’s a family tree of ambitious approaches to data. An objective (and interoperability-oriented) map of the territory would probably look like a sprawling Venn diagram of toolchains and technologies, each of which plays nicely with its neighbors but laboriously with its cousins. As with any family tree (of language, of humans, or of technologies) there has been some serious drift over the years, and specialization, and adaption to different environments. And like languages, technologies can also drift into mutual incomprehensibility after enough drift and specialization: dialects becoming languages, translators become necessary, and thus dictionaries and reference grammars becoming necessary for scaling them up.

I’d like to sketch out one possible map of the territory, for organizing backlogs and futures and community governances and whatnot.

I’ll do my best to keep it funny and goofy, but this is basically a longform report-out of months of research and conversations and dredging github threads to tease out the shape of interop pasts and futures, so forgive the passionate verbosity.

From Principles to Systems Made Up of Components

The broadest and currently-canonical definition of “what IPFS is” can be found in Robin Berjon’s “IPFS Principles” document, which defines the particular IPFS flavor of Postel’s Law by which arbitrary data is broken up into 1 or more content identifiers and passed around a system between storage providers and consumers. This first-principles approach emphasizes the ambient verifiability, and rightly so–it’s quite the game-changer! Berjon extracts from the atom of the Content Identifier (hereafter CID) a micro-specification for determining (in the style of an IETF RFC) what the minimal requirements are for an IPFS system.

By Berjon’s pragmatic definition, any two systems that can exchange CIDs and use them to exchange data have just federated their two systems into one meta-system, specifically, one interplanetary file system. In this definition, any piece of software that can translate local context and outside data into the lingua franca of CIDs is a piece of IPFS software, or more precisely, an implementation of one or more pieces of a IPFS system.

So far so good, but the slippery bit is going from discrete software components to the boundaries of entire systems, each of which definitively is or isn’t doing an IPFS. The verification afforded by using CIDs is strong enough to cross a trust boundary, sure, but that just decouples the parts of the system and makes it harder to draw the boundary around the whole thing. For example, Berjon’s definitional excursus on the theoretical CID-verifying JS code snippet is telling, because nothing says “trust boundary” like “arbitrary JavaScript running in the end-user’s browser”. Implementing IPFS over the hostile terrain of the world-wide web requires a lot of components to work together to make CIDs a narrow waist of trust; but are they really working together in one system anymore?

I would argue that Berjon’s definition of a CID-based imperium defines the language family of IPFS (let’s call it Latin), but it won’t settle territorial disputes about where to build walls and where to build bridges (much less those about who pays for them). With technologies as with languages, these disputes about where the outer and internal boundaries of IPFS lie offer lots of insight into the complementary but in some ways competing systems and optimizations within it. For this reason, I will intersperse my meandering argument with little explanatory excurses about conceptual edge cases, places where the common language broke down and unmet needs for translation sit uncomfortably in the common backlog. Each of these contribute to the broader argument about federation and decentralized progress, but in their own right, each excursis is a profile of a distinct language that needs just a bit of boundary-setting and specification to mature, to stabilize, to grow… and maybe even to find a bit of Language-Market Fit!

Content-Addressable Systems for Graphing Data that May or May Not Be Interplanetary File Systems

If we zoom out a little bit from Berjon’s atoms and component to the level of entire data systems, the server kubo would be a great starting point to define the layers of a typical IFPS system.

Implemented in Go and accessible in many serverized wrappers and interfaces, is usually held up as the “definition by example” of what IPFS is.

It is nominally the “reference implementation” of the whole system, in that if you install kubo with default settings in two different places and tell them to sync to one another, you have created an IPFS subnet which automatically contributes any data you give, as well as its compute and storage, to the public DHT.

Your two kubo servers are IPFSing, clearly.

To keep layering on more cheeky wrinkles and jowls on my extended metaphor, the global system of kubo-centric networking is the Holy Roman Empire, or at least the Catholic Church.

kubo is great at working with (and translating from the dialects of) a wide array of components specialized to different conditions and making it all one gigantic global data substrate.

It is the heart of every end-to-end system that can be called IPFS today.

But this is a very tautological way to define systems. I want to define other systems (and how they could or could not be IPFS) by starting at the other end of the spectrum, the least kubo-friendly, and work our way back.

Excursus: iroh

On the other end of the consensus spectrum is iroh, a commercial data-syncing platform and toolchain from n0 computer with no dependencies on IPFS toolchains.

Here, whether or you consider iroh an end-to-end IPFS system depends largely on your interoperability requirements and your use case (in a word, your definition of IPFS!).

By Berjon’s definition, it is unambiguously an IPFS “implementation”, a fully-fledged language in the family tree, although any number of technicalities could be used to declare it only conceptually akin, a free-port pidgin that picked up some words but not the deep structure of the parent-language.

Factually speaking, it uses multiformats and familiar CIDs and meets all of the requirements in Berjon’s definition, without being effectively interoperable with kubo.

The list of differences from their documentation is telling, and a useful place to start defining the “stack” of a CID-based data system, and its translatable (or not) interfaces. I’ll revisit this chart at the end of the article in expanded form.

| Concept | Iroh | Kubo |

|---|---|---|

| CID Usage | Used for root hashes on the Blob layer | Used for all blocks |

| Hash Function | BLAKE3 | Various, SHA2 by default |

| Maximum Block Size | none | 1MiB |

| Data Layout | Key-Value | Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) |

| Data Model | “Bring your own” | IPLD or “Bring your own” |

| Syncing | Document Layer | none |

| Networking Stack | Connection Layer | libp2p |

| Public Key Cryptography | ED25519 Keys | Various, ED25519 by default |

| Naming system | none | IPNS, DNSLink |

| Content Storage | User Files + Cache | Internal Repository |

| Verification Checkpoints | send and receive | receive |

Let’s try reorganizing this list a bit, trying to think less in terms of all the many incompatibilities and more in terms of subsystems and dependencies.

- “Maximum block size” is a point of comparison lost on those lucky souls who have never designed a file system or database, or who don’t stay awake at night wondering whether

irohis an IPFS implementation. It refers to the maximum size that a CIDs referent can reach before needing to be “wrapped in a file”, i.e., a map of multiple CIDs to multiple blocks of data.- In a sense, this ceiling beyond which inputs must be chunked created the “file system” that the FS in IPFS stands for. It also kept CID resolution simple (if necessarily recursive) when applied to all the world’s data while preserving its “logical units” loyally.

- Data Layout is an even wonkier point of comparison, which basically refers to that recursiveness created by the file system by which resolving a CID to a map of blocks requires navigating a DAG rather than a one-step CID–>reference resolution. It’s not so much that kubo doesn’t organize its data in a key/value store… it’s just that it ALSO layers on a DAG since those values can contain further keys.

- IPLD is a low-level data model that, applied universally and interwoven with the above assumptions, creates many efficiencies and shortcuts. You could think of this as a minimal transformation of inputs that reduces overhead efficiently at the expense of needing consumers and distribution to share the same assumptions (and dependencies). “BYO data model,” by contrast, requires your consumers and distribution network to share that set of assumptions and dependencies instead!

- IPNS is a handy add-on component that adds a mutable pointer system to the DAG… but has a strict dependency on the DAG, which in turn was necessitated by the file system and its block size ceiling.

Hashing only with Blake3 versus the great many hash functions encodable as multihashes is a huge difference, one which troubles my extended metaphor considerably since multihash is, basically, the translation layer for CIDs.

But I interrupted the re-ordering exercise to dwell on it because it is a massive difference, which relies on certain properties of Blake3 as a cryptographic function.

Basically, Blake3 is a younger, not-yet-entirely-mainstream hash function optimized for large files and streams; it bucks the trend that justified the block-size ceiling in the first place, since it parallelizes compute on large inputs and allows verification-as-you-go for streams.

iroh choosing to rely exclusively on Blake3 as its only hash allows iroh to drop the block ceiling and the DAG and filesystem that follow from it, explaining almost all the downstream incompatibilities enumerated in the above chart.

Dropping the DAG and filesystem drastically reshaped what the core library of iroh can do, and the makeup of the whole system around it, how it distributes compute between layers, and even its trust model.

The row Verification checkpoints makes this quite explicit: since each iroh instance handles flatter key/value data stores, which it partitions into the logical units of the Document Layer, the logistics of sharing and verifying are totally different– it can verify all data on its way out to have a flatter trust system, making for a totally different system architecture.

The only differences not downstream of limiting the Blob layer to blake3 are the narrower choice of keys used to identify actors in the syncing network and the analogous move to sidestep libp2p and use QUIC networking exclusively for the iroh network.

(Like blake3, QUIC is younger than the block size ceiling and the libp2p networking stack built to help kubos find each other across all the NATs and networks of the internet.)

Both of these choices greatly reduce the work required of the core library, by dropping much optionality (much of it related to legacy compatibility).

All of these choices are surmountable, but require data from one system to be packaged up into a discrete unit, translated, and “notarized” by a checkpoint between the two systems. Tellingly, this work is, years into the project, still TBD – who should do it? Who needs it? Who pays for it to be done?

This is actually the question begged by Berjon’s slightly circular definition of an IPFS system as one that can translate its CID-handled data in a way that will be parseable to… another IPFS system (emphasis mine):

[An IPFS implementation] must expose operations (eg. retrieval, provision, indexing) on resources using CIDs. The operations that an implementation may support is an open-ended set, but this requirement should cover any interaction which the implementation exposes to other IPFS implementations.

By this functional definition, iroh is definitively becomes an “IPFS system” when it gets a scaleable translation mechanism for firehosing data tokubo and helia instances at each “exposure” to them, which kicks the can down the road since on both sides of that exposure an interface needs to be implemented.

And what possible exposures could there be?

If logical units are being chunked and indexed and overlaid so differently, where could the two systems realistically compare notes or trade data?

For this we’ll need to rephrase the feature comparison above to a comparison of architectures.

Mapping the Minimal End-to-End IPFS System

Here is a bog-simple architectural breakdown of an IPFS system, that we can use to schematize before applying to the morass:

- Data ingress: data gets turned into CIDs.

- Optionally, the ingress system can introduce helpful abstractions like CAR files, data blocks, recursive DAGs, etc. Each of these may constrain (or be motivated by) a corresponding choice at one or more of the other three layers.

- Sync: Data get synced and replicated and persisted by their CIDs.

- Networking can be optimized for global sync, e.g. via

libp2p, and/or combined with allowlists and conventional authorization systems, depending on the mode and permissioning model chosen. - In its simplest form, all data that comes in will be shared to peers; beyond rate-limiting, any other policy usually requires awareness of abstractions or introspection, thus coupling to choices at other layers.

- Networking can be optimized for global sync, e.g. via

- Routing: The data and information about networking and routability get indexed and advertised to

- Advertising content to consumers, TTL, and other persistence consideration add more supporting abstractions (e.g. IPNI records, delegated routing, bitswap, etc.).

- Indexes and distribution networks can scale up to global scale, as on the public DHT or “IPFS mainnet”, or skew simple and static in bounded networks, such as on subnets, traditionally-enforced trust boundaries, by API keys, etc etc.

- Optimizing for global distribution favors global-scale “gateways” and a distinction between ingress/origination nodes and “persistence nodes” (F.K.A. “pinning services”).

- Fetch: The last mile of dereferencing a CID from a potentially untrusted and often unfamiliar node.

- Depending on trust boundaries, fetch can incorporate a verification step to reduce the trust requirement on “gateways,” making “delivery” a networks - indeed, it probably always should

kubo can do all 4 of these functions, and in the early days of IPFS, various kubo instances configured differently actually did all 4 in every IPFS system.

Client diversity has grown steadily over the years, as has specialization and helper-components like ipfs-cluster for load-balancing huge installations and elastic-IPFS for hyperscaling ingress.

But the important part to note, as newer installations focus on drastic changes on one or more of these layers, is that they are not cleanly decoupled yet;

choices at any layer of the four constrain and influence choices on the others, often introducing abstractions and complexity and overhead.

Finding a schematic, simple language for these optionalities and cross-dependencies doesn’t just get us a working definition of an IPFS system and an apples-to-apples rubric between them: it also clarifies boundaries and tradeoffs, letting distinct languages “compete” less and complement one another more.

Abstracting out public data networks from the Amino “Mainnet”

While a lot of design choices are downstream of the block size limit and the efficiencies of scale created to manage huge datasets of blocks below that size limit, just as many (maybe more) are downstream from the choice to support the public DHT, or as it is known in 2024, the “Amino network”.

“Private network IPFS” is often described in documentation and public-facing materials as a kind of useful side-effect of the IPFS toolchain originally designed to work as a global peer-to-peer network.

kubo or helia can be easily configured to run well in a “private network mode”, but they still building internal indexes and broadcast-lists optimized for a global distribution network, which private-network data can be flung back into by an accident of configuration or an errant peer connection.

The fission.codes blog post that first popularizing the nickname “Mainnet” for the “Amino” public DHT helpfully extended this blockchain ecosystem analogy by pointing to two “private networks”: source network and quiet.

I would argue they are still IPFS systems, by Berjon’s definitions and by mine above.

What they are not is public-data systems that publish and persist all ingressed data on the Amino “Mainnet” or any other global public data layer.

Other public-data networks could be supported by or even deeply integrated into an IPFS filesystem: one that, say, broadcasted CAR files with BitTorrent-style magnet:// links on the mainline DHT, or one that swapped out IPNS for pkarr and/or did:dht to advertise peerIds or other key-based identities.

Or, even more abstractly, the public/private binary might be too simple for the boundaries of the data an IPFS governs: data could default to public by a kind of deadman’s switch, novel abstractions could create credible exits in either direction, etc etc.

Excursus: LUCID

While iroh shows a way forward for a branch of the family tree that traded blake3 for the Amino DHT, Lucid presents an even narrower cross-section of the CID-powered future, limiting itself not just to blake3 hashes, but to a narrow set of CID expressions generally.

This creates some useful side-effects: deterministic CID for any given input, turning each CID into a checksum for verification anywhere blake3 can run and a deduplication mechanism; lexically-sortable CIDs, etc.

This also sidesteps the compatibility question, since kubo or helia or w3up can also produce these same CIDs if configured appropriately, and each could ingest, persist, broadcast and index them as normally (even if not in mutually-intelligible ways).

To put it another way, LUCID defines an opinionated ingress dialect that subsets that of the iroh ingress configuration options.

It similarly leans blake3 and leans on incremental verification of large files to triage the architectural problems inherent to dereferencing a CID from a large file. Like iroh, inputs smaller than the Bitswap block size limit (which is effectively the Amino block size limit, for now) will generate CIDs that can be synced and indexed in Amino.

Unlike iroh, however, no CAR-like collection is defined, prefering to maximize for CIDs as unique and opaque identifiers pointing to single resources without recursion or abstractions.

This allows for URL-centric use-cases similar in shape to checksum-based prior art like Sub-Resource Integrity and Data URIs.

Abstracting out the IPFS from the Web as a URL-to-resource key/value store

While iroh was optimized for a distribution network architectured very differently than the Amino network, LUCID is optimized for web distribution, WASM, and other futures.

LUCID strives to be the most lightweight path to a worldwide web that could be infested by the CID brain virus without having to take on any IPFS dependencies, routing schemes, protocol handlers, or anything else.

Lucid establishes a path for a few hundred lines of javascript to secure ingress and fetch so that the entire (conventional, HTTP) web could be the distribution network for CIDs.

In this future, data can travel around between web servers and crawlers and backup services and security registries tamper-proofed by CIDs, but still live happily in today’s domain-locked browser security model and architecture. As distribution networks go, there are more immature ones!

Excursus: web3up, CAR Envelopes, and Content Credentialing

Web3.storage is a Protocol Labs-incubated startup that, like iroh, needed a different featureset than conventional IPFS to optimize for various aspects of their product offering: location-aware hosting and fetching, object-capability authorization woven into the IPLD graph alongside the data itself, heavy and novel usage of IPLD over discrete resources, etc etc.

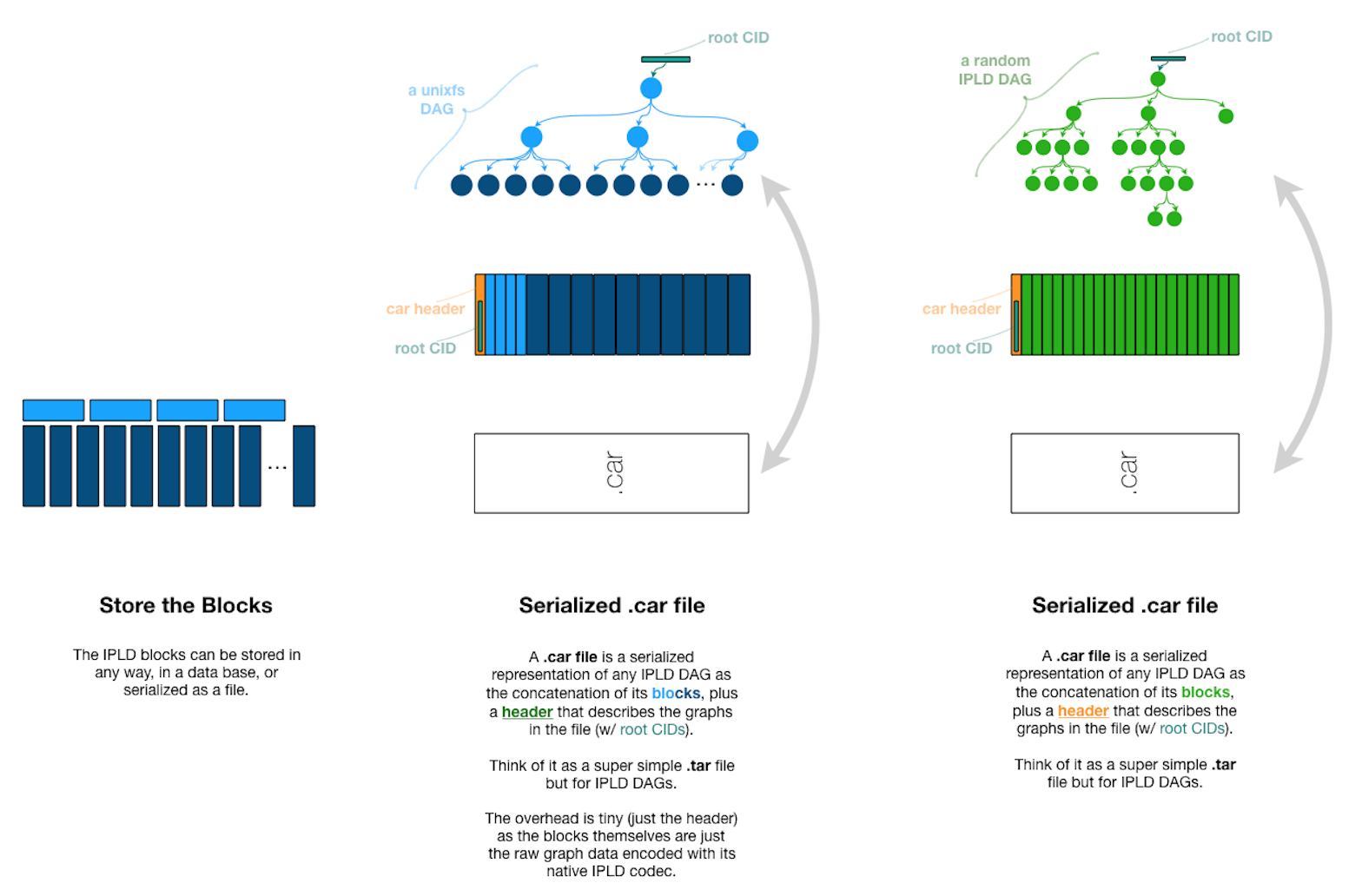

The “CAR file” (Content-Addressable aRchive format), meant to rhyme with the Unix “tar file” (originally used for magnetic-Tape ARchives), predates Web3.Storage’s further elaboration of the format, but what’s relevant to this discussion is what they enable: translation between implementations aware and those unaware of Web3.Storage’s IPLD-native storage system.

For those unfamiliar, the illustration above sums up what a .car file is and why Web3.Storage made them a first-class citizen in all their tooling, to smooth over interop between their IPLD DAGs and the UnixFS-based prior art, for which they were simply vast collections of smaller-than-usual blocks.

This one simple trick (ensuring that all “uploads” and “downloads” to the w3s network were formatted as a CAR file so that backing systems in the Amino Network could better parallize them and handle them as “raw blocks” and sidestep their usual UnixFS optimizations) made it possible to share infrastructure originally designed for and optimized for UnixFS data to smoothly take on new kinds of throughput.

(Web3.Storage shouldn’t get all the credit, of course, as Filecoin also needed CAR files to smoothly interoperate with Amino while preserving the deterministic “snapshot” capability its usecases required).

What’s instructive here, to my mind, is that the .CAR file offers a kind of well-specified “outer envelope” that can be wrapped around CIDS that might otherwise confound interoperability and translation. “Checkpoints” between systems that only accept and produce CAR-wrapped data is certainly one way to aid not just interoperability between today’s systems but forward- and backwards-compatibility over time and for archiving data made by deprecated or rare tooling.

Abstracting Out Determinism from Optionality

Further down the road of a backwards-compatible but divergent subsystem within IPFS, the same team came across further challenges. As the specification for Content Claims formulates the problem,

File reads in this system requires that two entities, the client and the peer serving the data, both support an IPFS aware transport protocol.

Decoupling transport from IPFS “awareness” (and tooling, and abstracting extensions) was thus necessary to host data (however “dumbly” or unaware) on conventional infrastructure, and this required a kind of translation document or “bill of lading” at the borders of the IPFS-aware system. This meta-awareness document is called a “Content Claim” and it goes further than a CAR file in scaffolding interoperability across the 4 layers of the system.

Content claims contain the following class of statements about input data, the CIDs they generated, and what can be known in advance of resolving those CIDs:

- location claims, including conventional/non-IPFS “locations” where the content of a given CID can be had (whether in addition to, or instead of, through Amino’s CID-advertising process)

- inclusion claims, to frontload or guarantee the “recursion” inherent in UnixFS and IPLD alike (or to allow parallelization rather than recursion, e.g. for systems with different runtime memory/network-load tradeoffs)

- equivalence claims between multiple CIDs derived from the same input data, use cases for which could include:

- the Blake3 hash of a large file generated by a LUCID implementation or

irohand the Blake3 hash of the same large file passed to a UnixFS implementation that broke it up into standard blocks first - the native CID of a file long-ago encoded, and the same file’s equivalent in a narrow profile like LUCID, to allow for deduplication and “deterministic” CIDs

- the Blake3 hash of a large file generated by a LUCID implementation or

This kind of equivalence might seem a kind of hack or stop-gap in the current highly heterogenous and multi-use-case IPFS family, but I would argue they are a valuable primitive and the best thing we have in the medium-term future for bridging gaps between divergent optimizations and form-factors. Furthermore, each Content Claim answers, on behalf of a given set of data, what I have been arguing the implementations themselves need to answer at the component layer: what dialects they can produce, and what dialects understand.

Which way, modern file system?

I want to close the loop on a functional definition of what an IPFS system is, as opposed to an IPFS component or “implementation.” The excurses and 4-layer model have sketched out an architectural framework, but some synthesis is still needed– and some blood sacrifices.

In general, compatibility both backwards- and forward- tends to become a bigger and bigger burden as any system incorporates more use-cases and form factors; the question is not one of whether to deprecate, but on what timeline, and with whom punished for upgrading too fast or too slow.

My intuition as IPFSCamp 2024 approaches is that we are increasingly faced with questions not of “what is IPFS” but rather, “what is mandatory for a given IPFS among many.”

The key questions seem to be:

- Is support for the global Amino network integral, or optional, for all IPFSs?

- Even where it is supported, is “advertise all CIDs to Amino” a sensible default configuration going forward, or one that should be sandboxed to ensure safer segmentation and more diverse and integrated authorization schemes?

- Are UnixFS and IPLD on equal footing? Is translation between the two and smooth coexistence a completed project? What are next steps for IPLD, and who needs them?

- How to establish perimeters or subsystems within which specific narrow dialects (UnixFS-only, LUCID-only, libp2p-only, QUIC-only, etc) can be safely assumed and fine-tuned?

- How to establish scalable checkpoints where data can flow out of those perimeters, while filtering or translating all data coming in?

Regime Change

Protocols and file systems and data models have fairly straightforward definitions, usually functional ones based on conformance regimes. For example, since HTTP is governed by a fairly hardened protocols, you only have to read a few RFCs closely to write a test that can separate the HTTP-practicing wheat from the troublesome chaff cluttering up the empire of HTTP. We use the slightly creepy metaphor of regimes for this kind of boundary-enforcement because testing makes boundaries as clear as a heart attack, or an army: they discipline networks, markets, and communities.

In IPFS, there are a lot of specs defining the major components and interfaces of IPFS specifications. Since so much weight rests on the “gateways” serving IPFS data over the web, and so many companies over the years have stood one up their own independent gateways, a full conformance test suite was established, and many specifications contain test vectors to help implementers know they have implemented the specs they are targeting flexibly enough to exchange data with others our decouple from today’s infrastructure and assumptions smoothly.

Truly going through with that decoupling, though, would require us to have detailed “profiles” for how to use each component per dialect, and conformance tests and test vectors at more places than just the gateway interface.

Above, I spitballed a four-layer simplification of the IPFS end-to-end system for the sake analyzing some illustrative example of intra-dialect translation. I’m sure someone will eventually convince me there are effective three, or six, or five layers worth segmenting out, but for the sake of some day finishing this overlong article, let’s call them four for now and decouple them at least at a high level:

- CID generation –> Ingress dialect

- Peer Networking –> Networking dialect

- Indexing –> Data Circulation dialect

- Hosting-Consumer Interface –> Fetch dialect

Ingress Dialects

Ingress profiles are pretty self-explanatory: the configuration of an ingress client often accomodates a lot of optionality, and one ingress client can often be configured to “mimic” another and produce the CID that this other client would have. Formalizing this with an IPFS spec might make interop targets easier to backlog, roadmap, and prioritize.

Formalizing this kind of CID parameterization would also allow for “CID translation” to be scaled up as a kind of public utility or shared codebase as well. Parameterization and corner-case trapping could make bidirectional translation of CIDs easier to engineer. Some CID parameters and multiformats codecs (including internal ones) have historically been underspecified, and one way of forcing the issue would be withholding or retroactively removing “final” status for any codec that is unsufficiently specified to be reproducible, lacking in test vectors or testing regimes, etc.

It also bears mention that CID translation is a kind of inefficient “last resort” for interop between IPFS systems: it decomposes a network to its smallest unit (the CID) and recreates it in a new language to be ingested in another network. In many cases, it would be preferable to instead make living systems interact in the present (and at system-scale) at one or more of the other three layers in a way that is aware of differences of CID generation. This could well require, at those layers, for “foreign” CIDs to be routed and handled differently, accomodating (if nothing else) the somewhat expensive work of translating CIDs for the benefit of the rest of the system.

Networking Dialects

Here there is much less diversity, partly because libp2p has been so useful for stitching servers almost everywhere and anywhere into the Amino DHT, so few other dialects have evolved.

Historically, libp2p was the default option both for automagically forming synchronization networks on a peer-to-peer basis, AND for the formation of a broader and more heirarchical/scalable “content routing” (i.e. CID propagation) network for long-lived content.

These two distinct kinds of networking operations used very similar mechanisms, and both required all participants to support abstractions like IPNS and the ingress profiles these depend on.

Decoupling them, and allowing them to be configured separately, might be useful, and necessary for making the other 3 layers more independent and swappable.

For example, the kind of perimeters a system already needs might make libp2p and/or Amino optimizations (with all their dependencies and abstractions in tow) a bad fit for some use-cases.

For example, systems that, by design, operate on a single network or cloud provider, or systems that already have authorization deeply woven into them, might not need either.

Little work has been done to specify this layer, partly because interoperability at this layer tends to happen as an ad hoc matter, if at all.

It might be necessary if evolution continues on non-Amino systems that might develop a need to federate to one another.

It could also be worth specifying sooner for projects like “supersetting” Amino and making it work more smoothly with other global-scale DHTs like the Mainline DHT that runs pkarr and BitTorrent, or deeper integration with “composable” blockchain data plumbing like Celestia.

Data Circulation Dialects

Since Amino usecases were prioritized for a long time, lots of optimization for massive-scale CID lookup sharing between [all] directly-connected peers and massive advertising of each CID were baked into kubo and other implementations.

Over time, even these optimizations were not enough and hyperscaling components like Elastic IPFS and IPFS-cluster were evolved to accomodate usecases where millions of CIDs were added every day to massive stores, for whom even indexing CIDs for advertisement became a bottlenecking problem at scale.

Similarly, Bitswap (the peer-to-peer protocol which, as the name implies, maximally spreads indexes and advertisements around between central nodes in the system) became a kind of bottleneck even for Amino-focused use-cases, much less the divergent ones.

Decisions at this layer are highly determinant for the other layers, so I think architects deciding which “dialect” of IPFS is best for their use-case or system should probably start here. For them, these might be the up-front questions to answer in a first pass of research:

- Is the desired end-result THE global, public DHT (Amino) or, for that matter, some other global, public DHT?

- If not, what kind of security perimeters need to exist within the system, if any?

- Does data need to flow both ways everywhere in the system, or are some flows unidirectional?

- Does each logical unit of data have a TTL, or is it permanent? Should there be garbage collection, based on frequency of access if not by expiry decided in advance?

- Will your data be append-only? Or (at least from certain views) mutable?

The answers to these questions can determine whether (and where) a given system will need things like ipns for mutability, bitswap for syncing, ipni for advertising CIDs through channels other than the Amino DHT, etc.

If it only needs them in certain places, figuring out “checkpoints” beyond which they are not needed (and even awareness of them is not needed).

Fetch Dialects

We could think of the trustless gateway project as the design precedent for a more flexible and interoperable architecture. The trustless gateway could be thought of as a “checkpoint” where IPFS-aware (but system-unaware) counterparties bridge a perimeter: CID verifiability as no-guarantees egress protocol. Or we could think of trustless gatewars as “border towns” in the extended metaphor: fortified little Andorras, even.

There are already three trustless gateway “modes” asking that data for a given CID be returned in modern/IPIP-0412 CAR envelope, raw IPLD (translating between block-ceilinged CIDs and iroh/lucid-style unblocked clients), or IPNS-record (updatable pointer signed by originator, trustable only relative to that originator’s reputation in an IPNS identity system). Reading between the lines a little, it is obvious that these three distinct modes correspond to radically different assumptions about the architecture in which those modes would be useful.

Just a little specification about what a trustless “mode” can be (i.e., do they always map 1:1 to an HTTP header? what gateway or client behaviors MUST and MAY they specify?) would go a long way towards making Trusted Gateways powerful enablers of reliable and mature translation.

If these modes were a little more detailed (i.e. if they were profiles of an architectural component rather than just modes a trustless gateway component can be configured to run), we might get a set of defaults or pre-configurations for gateways that are ready-to-go, just-add-water components of a system that speaks CID at its edges… while allowing more freedom to diverge within their system.

Excursus: Segmented NFT Example System

To make this more concrete, many systems I’ve seen have CID generation strictly segregated from CID publication already, and can thus greatly simplify a system with two distinct parts. Think, for example, of a system that only generates CIDs at, say, the minting process of a batch of NFTs, a process which includes very few actors and components. Once that corpus of images and metadata has been “CIDified” and each NFT has the right URIs encoded in it, this static SQL table of a system switches gears, and suddenly each of those CIDs needs to be available performantly and globally over conventional web technologies.

In this case, how the subsystem involved in generating CIDs bootstraps its networks and passing along its outputs to a more conventional publication system is very different from the network profile of the “mini-gateways”. The first system might need to optimize for privacy, confidentially, obscurity, or even security-by-obscurity, hiding from attackers behind cryptic networking mechanisms. The latter, on the other hand, has a fairly conventional CDN-like networking and performance profile, which might benefit from knowing literally nothing about the former system, lest it be compromised somewhere in its many attack surfaces.

This latter system, which I’m cheekily calling a “mini-gateway,” might be thought of as an “output only”, non-IPFS subsystem of a greater IPFS configuration.

This whole output-only system can be handed a bunch of URLs that either are or contain CIDs and referents for each representing various content-types and be completely “unaware” of all the IPFS that generated this mapping.

Indeed, that might even be mission-critical for such a use-case.

Exactly because it’s so mission-critical, this entire latter subsystem (which the outside world continues to call “pinning”, against years of trying to unmeme it) is often offloaded or outsourced. In the best of cases, this content delivery subsystem is handed off to a well-thought out service provider business model like that of Pinata or Web3.storage, resulting in SLAs and a defensible business niche for middlemen that make IPFS “just work”. In the worst of cases, lazy web3 SDKs misinform their developer users about the mechanics of Amino DHT and IPFS gets a reputation across entire communities as “not working at all”. The difference between these two is a difference of narrative downstream of how we document the capabilities of IPFS systemS… the plural could be really helpful here.

Next Steps

Mingling history, speculation, and implementer feedback as I have might not lend itself to clear next steps, but I can just put those baldly:

- I want each piece of software to have more clearly defined interoperability targets with the rest of IPFS, in the form of novel approaches and dialects that it can implement and declare (in some standard, translation-powering syntax) at each of the four levels described above.

- After adding missing features, many pieces of software will need to refactor their interfaces to foreground support for multiple (sometimes even mutually-exclusive) modes, each optimized for different “dialect” targets.

- Where multiple options are enabled by a given piece of software, it should be easy to configure subsets of that optionality– “run in Amino mode only” for example, or “disable all CID advertising”. Much of this is already built, but needs to be foregrounded in documentation if any users (or even more crucially, evaluators) are going to understand how many IPFSs they have to choose from.

From here to that future, there’s a whole lot of specifications to write and implement. But on the other side of that work, it becomes a lot easier to maintain up-to-date information on each piece of IPFS software about what other software it works with, and how to configure it for profiled usage. A caniuse.com for IPFS is easy to maintain once its inputs are specified and a v1 launched. It also becomes a lot easier to roadmap futures and features, or sell them.

Is it worth it? Idunno, I just work here, man.